| |

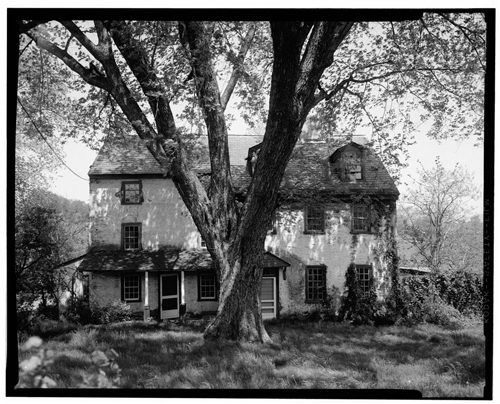

I've loved many different places and their people besides those: Jamestown, Rhode Island; Putney, Vermont; Kelly, Wyoming; Floyd, Virginia; Blairstown, New Jersey, all of New Zealand. Oceans, coves, woods, deserts, prairies, roads, trails, farms, bungalows, rowhouses, ballparks, ponds, and now specifically this Schuylkill River I grew up near but didn't really know until middle age when I started rowing on it. There seem to be a few ways that places can imprint on us: (1) immersion, (2) repetition, and (3) formation; that is to say, formative years. A fourth way, not to be minimized, is like a bolt of lightning—the way they describe love at first sight. It could be fleeting, like the first time I saw Yosemite outside of photographs (holy crap, it's real) but which holds no attachment for me now; or permanent, like Uig Sands in Scotland. Both were short stays, but only one place stuck. Why that happened is another story, which I share here. Observation is not enough. We documentary photographers observe and care but often move on, even emotionally. Compelling subject matter and surface visuals like the quality of light may have little to do with the imprint of a place, which may come from early formation or later immersion. You need not "observe" or "study" an imprinted place; you are simply in it or of it. That's not to say photographing a place can't make an imprint deeper. It took me a long time to realize, but a latent quest for my formative home place drove me, literally, all over America. For my first book, Fifty Houses: Images from the American Road (also shepherded by George Thompson, twenty years ago), I drove alone through all fifty states, rereading William Least Heat-Moon's Blue Highways and eschewing interstates. I made thousands of house portraits over seven years of road trips and chose just one for each state. By necessity, about 45 of those were bolt-of-lightning types. (Though the repetition of printing and reprinting them made most of them stick.) Oddly, I was rarely attracted to modern architecture. I'd grown up in a mid-century wood-and-glass split-level, surrounded by woods and adventurous friends. I was happy there, so why did I keep photographing traditional white farmhouses on open fields? In Indiana, Connecticut, Kansas, everywhere? It couldn't have been just my teenage painter self's Edward Hopper imprint, enduring as that was. Then one day I came across a photograph of a white stucco farmhouse in my dad's stuff. Whoa, there it is. Morgan Farm. I hadn't gone back far enough. This was my first home place, inhabited from birth to age three, a drafty pre-Revolutionary stone house with a big dilapidated barn amidst raggedy pastures in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. I hadn't gone back far enough in my own history to recognize that this house had imprinted on me more than any other. The formative imprint happened without my ever making a picture of it, but I'm glad someone did.

Now for the second story, a bolt of lightning. About eighty miles upriver from Morgan Farm is the Schuylkill River Gap at Port Clinton, where Berks County meets Schuylkill County and the Schuylkill and Little Schuylkill Rivers both carve their way through the Blue Mountains of Pennsylvania's coal region. I don't recall being there as a child. Now I walk the old towpath from the overgrown ruins of Lock 27 to the towering walls of Lock 25, the trail hugging cliffs above the pretty river. In winter when I photograph, I head back to the car by three o'clock or it will be dark down in there. It has its own micro-sunset. The gorge is rimmed with byways: the dry canal bed, the towpath, the river, the active rail line of Reading Blue Mountain & Northern (once the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad), and the repurposed Pennsylvania Railroad line, now the John Bartram Trail of the Schuylkill River Trail. The granddaddy Appalachian Trail intersects right here; it plummets down and climbs up this vertiginous space, its hikers stopping for repast in tiny Port Clinton's inn or candy shop. The river on summer weekends is populated with paddlers of the Schuylkill Water Trail. But who's there in November or February? A photographer struck by a bolt of lightning, at least. The Gap is brightly lit on one side, a smoky glow of bare branches, and it's damn dark on the other side, too much range for even a digital raw file to handle. Fine, let the shadows go black. The Gap in low light is like a concave Hopper house, a simple shadowed shape. Morgan Farm was long ago paved over for a corporate headquarters. The Schuylkill Gap is hidden, but you can find it. Follow the river. Winter is best. Copyright © 2021 Sandy Sorlien. All rights reserved.

|